Following is

the British Museum’s defence for their retention if the Parthenon Marbles. What do you think? Can you see the flaws in their arguments? We are happy to receive your comments.

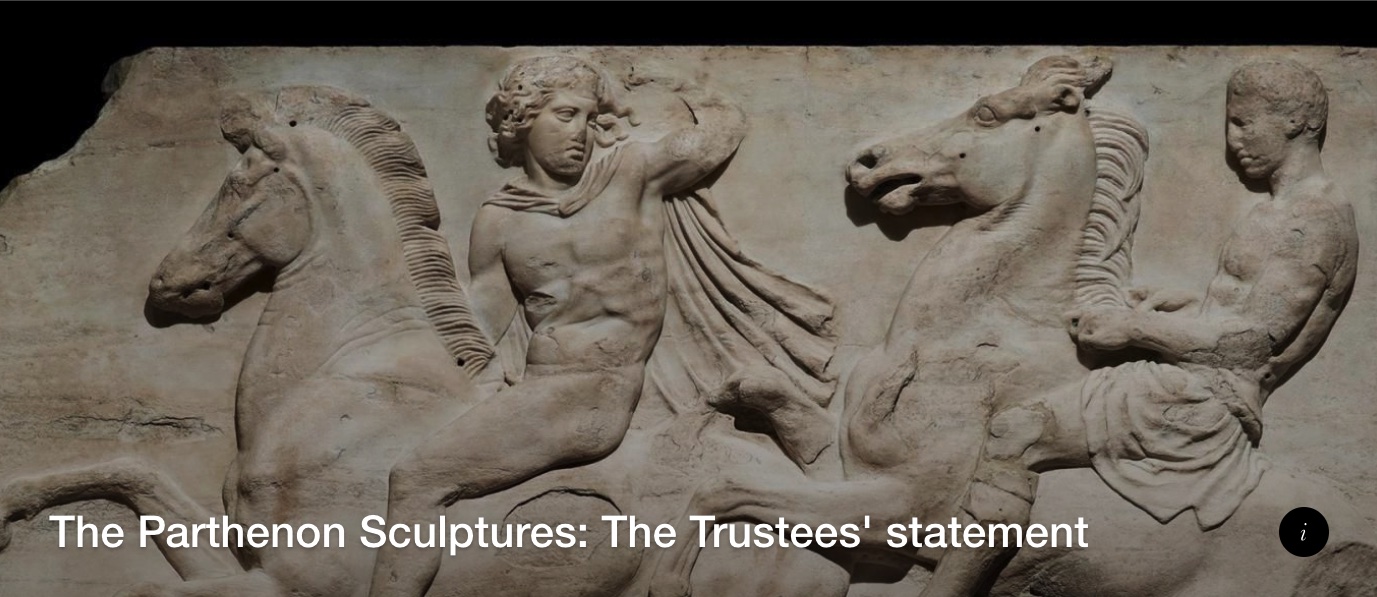

The British Museum tells the story of cultural achievement throughout the world, from the dawn of human history over two million years ago, until the present day. The Parthenon sculptures are a significant part of that story.

This is a dubious statement. It implies that there is a clear narrative in the collection which clear;ly there is not.

The Museum is a unique resource for the world: the breadth and depth of its collection allow a global public to examine cultural identities and explore the complex network of interconnected human cultures. The Trustees lend extensively all over the world and over 3.5 million objects from the collection are available to study online. The Parthenon sculptures are a vital element in this interconnected world collection. They’re a part of the world’s shared heritage and transcend political boundaries.

Detached as they are from the whole, stripped of context, the Parthenon Sculptures in the British Museum are unable to convey their own story. Standing in Room 18, where they arekept, does not allow the visitor to see any connections, they are isolated.

The Acropolis Museum allows the Parthenon sculptures that are in Athens (about half of what survives from the ancient world) to be appreciated against the backdrop of Athenian history. The Parthenon sculptures in London are an important representation of ancient Athenian civilisation in the context of world history. Each year millions of visitors, free of charge, admire the artistry of the sculptures and gain insight into how ancient Greece influenced – and was influenced by – the other civilisations that it encountered. The Trustees firmly believe that there’s a positive advantage and public benefit in having the sculptures divided between two great museums, each telling a complementary but different story.

The sculptures from the Parthenon remaining in Athens are still connected with the historic, mythic, and biophysical context from which they were created.

This is incorrect. About half of the sculptures from the Parthenon are lost, having been destroyed over the 2,500 years of the building’s history. The sculptures that remain are found in museums in six countries, including the Louvre and the Vatican, though the majority is divided roughly equally between Athens and London.

This statement deliberately minimises the impact of Elgin’s removal of sculptures from the Parthenon.

In the British Museum there are:

17 pedimental figures

15 of the 92 metopes, and

75.2856 metres of the original 159.7152 Meters of frieze.

Apart from the Acropolis museum there are fragments in other museums

This isn’t true. Lord Elgin, the British diplomat who transported the sculptures to England, acted with the full knowledge and permission of the legal authorities of the day in both Athens and London. Lord Elgin’s activities were thoroughly investigated by a Parliamentary Select Committee in 1816 and found to be entirely legal. Following a vote of Parliament, the British Museum was allocated funds to acquire the collection.

This is untrue. What is now modern day Greece was occupied by the Ottoman Sultanate. No official original documentation extending legal authority for Elgin, or any member of his team, to remove sculptures, or other elements, from the Parthenon has ever been presented.

Elgin took many other things from Greece and his team produced a form of sales catalogue prior to the British Government’s acquisition of his collection. Here is a copy attributed to his chaplain W R Hamilton.

The Trustees have never been asked for a loan of the Parthenon sculptures by Greece, only for the permanent removal of all of the sculptures in its care to Athens.

The Trustees will consider (subject to the usual considerations of condition and fitness to travel) any request for any part of the collection to be borrowed and then returned. The simple precondition required by the Trustees before they will consider whether or not to lend an object is that the borrowing institution acknowledges the British Museum’s ownership of the object. In 2014 the Museum lent the pediment sculpture of the river-god Ilissos to the State Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg, Russia, on the anniversary of that museum’s foundation. The Trustees frequently lend objects from the collection to museums all around the world, including Greece. In 2015–2016 the Museum lent 5,000 objects to hundreds of museums worldwide. The British Museum is the most generous lender in the world.

The Trustees’ policy and their willingness to consider loans to Athens has been made clear to the Greek government, but successive Greek governments have refused to consider borrowing or to acknowledge the Trustees ownership of the Parthenon sculptures in their care. This has made any meaningful discussion on the issue virtually impossible.

Neither of these claims is true, and the British Museum doesn’t argue this. The Trustees argue that the sculptures on display in London convey huge public benefit as part of the Museum’s worldwide collection. Our colleagues in Athens are, of course, fully able to conserve, preserve and display the material in their care. We admire the display in the Acropolis Museum, in which the Parthenon sculptures are complemented by casts of all of those in London and elsewhere, creating as full a picture as is now possible of the original sculptural decoration of the temple.

This isn’t so. Europe’s complex history has often resulted in cultural objects, such as medieval and renaissance altarpieces from one original location being divided and distributed through museums in many countries. Bringing the Parthenon sculptures back together into a unified whole is impossible. The complicated history of the Parthenon meant that by 1800 about half of the sculptures had been lost or destroyed.

This isn’t possible. Though partially reconstructed, the Parthenon is a ruin. It’s universally recognised that the sculptures that still exist could never be safely returned to the building: they’re best seen and conserved in museums. For this reason, all the sculptures that remained on the building have now been removed to the Acropolis Museum, and replicas are now in place.

The Trustees of the British Museum believe that there’s a great public benefit to seeing the sculptures within the context of the world collection of the British Museum, in order to deepen our understanding of their significance within world cultural history. This provides the ideal complement to the display in the Acropolis Museum. Both museums together allow the fullest appreciation of the meaning and importance of the Parthenon sculptures and maximise the number of people that can appreciate them.

The British Museum has a long history of collaboration with UNESCO and admires and supports its work. However, the British Museum isn’t a government body. The Trustees have a legal and moral responsibility to preserve and maintain all the collections in their care and to make them accessible to world audiences. The Trustees want to strengthen existing good relations with colleagues and institutions in Greece, and to explore collaborative ventures directly between institutions, not on a government-to-government basis. This is why we believe that UNESCO involvement isn’t the best way forward. Museums holding Greek works, whether in Greece, the UK or elsewhere in the world, are naturally united in a shared endeavour to show the importance of the legacy of ancient Greece. The British Museum is committed to playing its full part in sharing the value of that legacy for all humanity.